돌아가기 mosaics

imperial-overview

Imperial Mosaics in Hagia Sophia – Who’s Who and Where to Look

From Justinian and Constantine in the vestibule to John II Komnenos and Constantine IX, use this guide to decode Hagia Sophia’s imperial portraits.

12/10/2025

13 min read

Hagia Sophia preserves a small gallery of empire in shimmering glass and stone. This overview maps the major imperial mosaics and explains why they were made — gifts, messages, and memory.

Southwest Vestibule: Constantine & Justinian

- A 10th‑century panel shows the Virgin and Child flanked by Constantine (offering his city) and Justinian (offering Hagia Sophia).

- It visualizes the idea that rulers donate their greatest achievements to the Mother of God, grafting piety to politics.

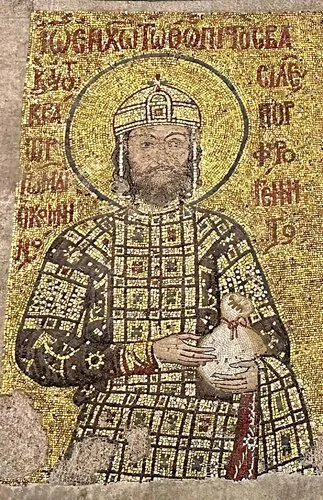

Upper Gallery: Komnenos Mosaic (1122)

- John II Komnenos and Empress Irene present offerings to the Virgin and Child; son Alexios appears on a side panel.

- Note John’s donor purse (imperial gift) and Irene’s distinctive Hungarian features as remembered in Byzantine style.

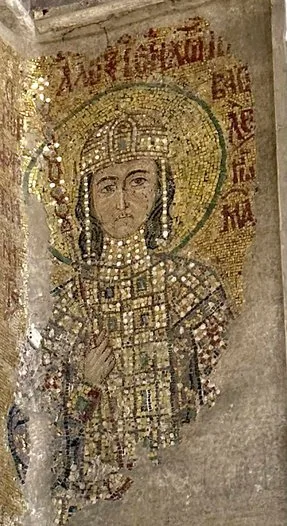

Upper Gallery: Empress Zoe & Constantine IX

- Christ Pantocrator blesses while Empress Zoe (with scroll) and Constantine IX (with purse) flank him.

- The heads were reworked — either updated for Zoe’s later husband or repurposed from an earlier pair.

Upper Gallery: Emperor Alexander (10th c.)

- A rare portrait tucked into a blind corner shows Emperor Alexander, who reigned briefly (d. 913).

- It’s one of the best‑preserved panels, likely painted over rather than plastered.

Inner Narthex: Imperial Gate Mosaic

- Above the gate, an emperor (often Leo VI; some argue Constantine VII) kneels before Christ with Mary and Gabriel in medallions. A text on the book proclaims divine peace and light.

- Today access is limited; consult current worship vs. tourist arrangements.

Reading the Code

- Purses signal donations; scrolls imply imperial decrees or pledges.

- Placement communicates hierarchy: Christ or the Virgin in the center; rulers at the sides.

Bottom Line

These mosaics are more than portraits. They are theater of legitimacy — emperors staging humility and generosity before the sacred.

저자 소개

Mosaic Storyteller

이 안내서는 하기아 소피아를 평온, 맥락, 배려 속에서 만나도록 돕기 위해 쓰였습니다—큰 사상, 잔잔한 기도, 빛나는 돌이 분명히 말하도록.

Tags

mosaics

emperors

Byzantine

upper gallery

vestibule

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment

Loading comments...